Introduction

This month, the American Psychiatric Association will publish the latest edition of its Diagnostic and Statistical Manual – the DSM-5. The manual contains significant changes to the diagnostic criteria for individuals with autism.

- The name of the category will be changed from Pervasive Developmental Disorder to Autism Spectrum Disorder.

- The four previous diagnoses: Autistic Disorder, Asperger’s Syndrome, Pervasive Developmental Disorder- Not Otherwise Specified and Childhood Disintegrative Disorder will all be combined into the single category of Autism Spectrum Disorder. Rett Syndrome will be eliminated from the manual since the gene that causes it has been identified.

- Three symptom domains will be reduced to two by combining the speech and social symptoms into a single category. The number of criteria has been reduced from 12 to 7 which reduces the number of possible combinations of symptoms to receive an ASD diagnosis.

- Severity codes will be added for each symptom domain, though the details will not be clear until the new manual is published.

- Criterion B4 adds a sensory component to the diagnosis for the first time.

Criteria

The new criteria under the DSM-5 are as follows:

Autism Spectrum Disorder

Currently, or by history, must meet criteria A, B, C, and D:

A. All individuals must have or have had persistent deficits in social communication and social interaction across contexts, not accounted for by general developmental delays, and manifest by all 3 of the following:

- Deficits in social-emotional reciprocity; ranging from abnormal social approach and failure of normal back and forth conversation through reduced sharing of interests, emotions, and affect and response to total lack of initiation of social interaction,

- Deficits in nonverbal communicative behaviors used for social interaction; ranging from poorly integrated- verbal and nonverbal communication, through abnormalities in eye contact and body-language, or deficits in understanding and use of nonverbal communication, to total lack of facial expression or gestures.

- Deficits in developing and maintaining relationships, appropriate to developmental level (beyond those with caregivers); ranging from difficulties adjusting behavior to suit different social contexts through difficulties in sharing imaginative play and in making friends to an apparent absence of interest in people

B. All individuals must have or have had restricted, repetitive patterns of behavior, interests, or activities as manifested by at least two of the following:

- Stereotyped or repetitive speech, motor movements, or use of objects; (such as simple motor stereotypies, echolalia, repetitive use of objects, or idiosyncratic phrases).

- Excessive adherence to routines, ritualized patterns of verbal or nonverbal behavior, or excessive resistance to change; (such as motoric rituals, insistence on same route or food, repetitive questioning or extreme distress at small changes).

- Highly restricted, fixated interests that are abnormal in intensity or focus; (such as strong attachment to or preoccupation with unusual objects, excessively circumscribed or perseverative interests).

- Hyper-or hypo-reactivity to sensory input or unusual interest in sensory aspects of environment; (such as apparent indifference to pain/heat/cold, adverse response to specific sounds or textures, excessive smelling or touching of objects, fascination with lights or spinning objects).

C. Symptoms must be present in early childhood (but may not become fully manifest until social demands exceed limited capacities)

D. Symptoms together limit and impair everyday functioning.

In addition, the DSM-5 introduces a new disorder, not on the autism spectrum, with the following criteria:

Social Communication Disorder

- Social Communication Disorder (SCD) is an impairment of pragmatics and is diagnosed based on difficulty in the social uses of verbal and nonverbal communication in naturalistic contexts, which affects the development of social relationships and discourse comprehension and cannot be explained by low abilities in the domains of word structure and grammar or general cognitive ability.

- The low social communication abilities result in functional limitations in effective communication, social participation, academic achievement, or occupational performance, alone or in any combination.

- Rule out Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD). Autism Spectrum Disorder by definition encompasses pragmatic communication problems, but also includes restricted, repetitive patterns of behavior, interests or activities as part of the autism spectrum. Therefore, ASD needs to be ruled out for SCD to be diagnosed.

- Symptoms must be present in early childhood (but may not become fully manifest until social demands exceed limited capacities).

Social Communication Disorder will be the diagnosis for anyone who meets all three of the Autism Spectrum Disorder speech and social criteria but none of the repetitive and restrictive behavior criteria. There is currently a gap between ASD and SCD, with no clear diagnosis for someone with all three speech/social domain criteria but only one criterion under the restricted and repetitive behavior/sensory domain.

Research Update

The following are brief descriptions of the research studies that have attempted to compare the old and new criteria for autism spectrum disorders. This list includes only those studies using the above DSM-5 criteria, not those studies done using previous versions of the new criteria.

As a brief explanation, the goal of the new criteria was to get the best possible combination of sensitivity and specificity of diagnosis. Sensitivity is the ability of the criteria to correctly identify all cases who actually have a disorder (to not miss anyone). Specificity is the ability of the criteria to correctly screen out those who do not have a diagnosis and eliminate false positives. The two are in tension with each other, as increasing one often reduces the other. In the case of the DSM-5 ASD criteria, the specificity appears to be excellent, but the research so far has raised concerns that the new criteria are too restrictive, thereby reducing the number of individuals who will be diagnosed (lower sensitivity).

McPartland, Reichow and Volkmar, 2012

This study looked at the records of 657 individuals, aged 12 months-43 years who participated in the clinical trials for the DSM-IV. It re-evaluated those individuals using the DSM-5 criteria and found that 39.4% would no longer qualify for a diagnosis on the autism spectrum. Those most affected by the change had IQ’s >70; sex and age were comparable in those meeting and not meeting the new criteria. By diagnosis, the new criteria excluded 24.2% of those with Autistic Disorder, 75% of those with Asperger’s disorder and 71.7% of those with PDD-NOS. One criticism of this study is that, since the DSM-IV criteria did not include a sensory criterion, no data was collected in the original files that might have fulfilled that criterion for the DSM-5.

Matson et al. 2012

This study screened a population of 2721 toddlers (age 17-36 months) at risk for a developmental disability. 415 toddlers met the criteria for an autism spectrum disorder using the DSM-5 criteria and an additional 380 toddlers met the criteria for either Autistic Disorder or PDD-NOS based on the DSM-IVR criteria. The researchers assumed that any child who met DSM-5 criteria would also meet DSM-IVR criteria since it is less restrictive. Their conclusion was that, potentially, there could be a 47.79% decrease in diagnosis as a result of the proposed criteria. Children who met criteria for PDD-NOS were disproportionately impacted – 79.94% of them did not meet the proposed DSM-5 criteria for ASD. A weakness of this study is that it did not actually diagnose the children. The data was based on care-giver reports.

Gibbs et al. 2012

This study was done in Australia and the team actually did new diagnoses on 132 referral cases. The subjects ranged from 2 to 16 years of age (Mean=6.06; SD=3.38). The ADOS and the ADI-R were administered to each child and their caregiver. A total of 111 children were diagnosed with Autistic Disorder, PDD-NOS or Asperger’s Disorder using the DSM-IVR criteria. Of those, 26 did not meet the criteria for Autism Spectrum Disorder using the proposed DSM-5 criteria – a decrease of 23.4%. Again, the children diagnosed with PDD-NOS were most impacted – comprising about 2/3 of the decrease. This study identified the requirement for two criteria under the Restrictive and Repetitive Behavior domain as the most common reason for exclusion.

DSM5 – Field Trials 2012

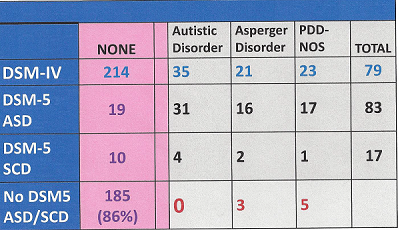

Dr. Susan Swedo, chair of the Neurodevelopmental Disorders Workgroup for the DSM-5, presented the results of the DSM-5 field trials for autism to the Interagency Autism Coordinating Committee in July, 2012. Her power point presentation indicated that the decrease in the number of identified ASD cases using the proposed criteria would be counter-balanced by the inclusion of some cases that had been missed by the DSM-IVTR. The field trials for ASD were done at two pediatric sites and screened a total of 293 children ages 6-17. Of these, 214 did not meet criteria under the DSM-IVTR criteria and 79 did. An additional 19 children met the DSM-5 criteria for ASD and 10 met the criteria for SCD. This may be the result of the addition of sensory criteria for ASD and the SCD cases may have come from the pool of children who would normally have fallen in another diagnostic speech/language category.

Of the 79 children who met criteria for an ASD under DSM-IVTR, 64 met an ASD diagnosis under DSM-5, which would be a 19% decrease. Including Social Communication Disorder substitutions is questionable because that will not be considered an ASD under the new criteria. However, the 19 additional children identified under DSM-5 balanced out the 15 that were dropped. 7 of 17 children, who met criteria for Social Communication Disorder, would have met the DSM-IVTR ASD criteria. These children likely represent the ones most at risk for reduced services. They represented about 9% of the children meeting the DSM-IVTR criteria.

Below is the field trial data as presented to the IACC in July 2012. The full power point is available at http://iacc.hhs.gov/events/2012/slides_susan_swedo_071012.pdf

Taheri and Perry, 2012

This Canadian file review study looked at 131 children aged 2-12 who had been previously diagnosed using the DSM-IVTR as having either Autistic Disorder (93) or PDD-NOS (36). The average IQ of the group was 46.28 (SD=25.6). Using the DSM-5 criteria on these cases resulted in a 37% reduction in ASD diagnosis: 19% in those with autism and 83% in those with PDD-NOS. The children with IQs of 70 and above were the most impacted (78% did not meet the criteria for DSM-5 ASD). Most noteworthy in this study was the finding that only about 20% of the sample population met each of the B2 and B3 criteria under DSM-5 (see above).

Mazefsky et al., 2012

This was a study of 498 high-functioning cases (Mean IQ 105, SD=16) who had been diagnosed for research purposes using the ADI-R and the ADOS (Module 3 or 4). All the individuals were verbally fluent and they ranged in age from 5-61 with an average age of 21.8 (SD=6). What this study showed was that neither the ADOS nor the ADI-R alone was sufficient to get good sensitivity using the DSM-5 criteria. This is not surprising because the ADI-R and ADOS are aligned to the DSM-IVTR criteria. Using the combination of both instruments together, the reduction in ASD diagnosis was 0%-14% comparing the old and new criteria. One caveat, however, is that this level of diagnostic rigor is not necessarily typical of what will happen in clinical practice.

Turygin et al. 2012

This study of 2054 toddlers aged 17-36 months in the Louisiana early intervention program found that the children who qualified for an ASD diagnosis under the DSM-IVTR and DSM-5 criteria (n= 279) were more impaired than children who only had an ASD diagnosis under the DSM-IVTR criteria alone (n=280). At the same time, the DSM-IVTR only cohort was still significantly more impaired than the atypically developing population that did not meet either set of criteria. This study suggests that there will be a shift towards greater severity in toddlers diagnosed using the DSM-5 criteria, while raising concerns about the needs of children who no longer qualify for a diagnosis.

Huerta et al. 2012

This is the largest and most rigorous study to date comparing the two sets of diagnostic criteria. It included 4,453 children aged 2-17 from three different existing datasets diagnosed using the DSM-IVTR criteria. Approximately 30% of the cases had non-verbal IQ < 70. The study showed a reduction of 9% in the broad spectrum using the DSM-5 criteria vs. the DSM-IVTR criteria. Specificity of DSM-5 criteria was equal to or better than the DSM-IVTR. One weakness of this study was that 75% of the total sample had autism, 22% had PDD-NOS and only 5% had Asperger’s syndrome so it was weighted towards the more severe end of the spectrum. Given the results of other studies showing the greatest impact of the DSM-5 will be on the higher-functioning individuals, the results of this study may not be generalizable to the whole population. In the sample, approximately 1.5% of the children did not qualify for a DMS-5 ASD diagnosis and would have fallen under the new SCD diagnosis (i.e. they met only the three speech/social criteria).

Beighley et al. 2013

This study included 459 children aged 2 to 18 (Mean 8.01, SD=3.5) and looked at challenging behaviors in children diagnosed with ASDs vs. controls. 219 children met the ASD criteria for DSM-5, 109 children met the DSM-IVR criteria, but not the DSM-5 criteria and 131 children met neither set of criteria. Overall, 33.2% of those qualifying for a spectrum diagnosis using DSM-IVTR did not qualify for a DSM-5 diagnosis. Using the ASD- Problem Behaviors for Children assessment, the study showed that while the DSM-IVTR children exhibited, on average, fewer behavior problems than the DSM-5 group, the two autism groups were much more like each other than like the controls. This raises concerns about the loss of appropriate behavioral treatments for children who no longer qualify for an ASD diagnosis under DSM-5. It also supports the finding in other studies, that children with less severe symptoms are less likely to receive a DSM-5 ASD diagnosis.

Wilson et al. 2013

This is a study of 150 clinically presenting intellectually-able adults aged 18-65 years (Mean age = 31). Only 2 participants had an IQ<70. It is the only study comparing the new DSM-5 criteria with ICD-10R and DSM-IVTR criteria that only includes adults. The initial screening in the clinic was done using the ICD-10R criteria. Comparing the ICD-10R diagnoses with the DSM-5, the researchers found that only 56% of the individuals identified still qualified for ASD under DSM-5. An additional 19% met criteria for a SCD diagnosis, which still left 26% with no diagnosis under the DSM-5 criteria. In a second comparison of DSM-IVTR and DSM-5 criteria, 80 adults met the DSM-IVTR criteria for an ASD. Of these, only 61 met the DSM-5 ASD criteria and an additional 12 met the SCD criteria. The DSM-5 criteria did pick up two ASD cases that the DSM-IVTR criteria did not. Overall, the study found the DSM-5 criteria to have good specificity compared to the DSM-IVTR/ICD-10R criteria, but to have low sensitivity in this adult population. The results suggested relaxing the algorithm would improve this situation.

Barton et al. 2013

This is a study of 422 toddlers aged 16.8-39.4 months (Mean 25.76 months, SD 4.44 months) who were recruited from over 80 sites in Georgia and Connecticut and included some toddlers at high risk for autism. All children were given the ADOS and ADI-R and 284 were diagnosed with ASD under the DSM-IVTR criteria. The authors wanted to assess the appropriate symptom cut-offs to qualify for an ASD diagnosis using the new DSM-5 criteria. By mapping the children’s records against the new criteria, they came to the conclusion that the most appropriate balance of specificity and sensitivity in toddlers would be to relax the DSM-5 criteria to 2 of 3 in the speech/sensory domain and 1 of 4 in the restricted/repetitive behavior domain. This resulted in a sensitivity of greater than 90% in their population.

Summary

Further studies are in process but, at this point, it is fair to expect that the implementation of the DSM-5 criteria will reduce ASD diagnoses at least 20% relative to the DSM-IVTR criteria. The data supports that the largest reductions will be in those formerly diagnosed with PDD-NOS. What remains completely unknown is whether a portion of that reduction will be compensated for by cases that the DSM-5 identifies that would not have met the DSM-IVTR criteria. However, the only data showing an actual increase in ASD diagnoses overall was the field trials which involved only 83 children at two clinical sites and included no toddlers or adults. The only other study reporting a substitution effect was Wilson et al., 2013 which showed a 21% reduction vs. DSM-IVTR even after allowing for the additions from DMS-5 picking up extra cases.

Below is a chart summarizing the studies to date with regard to the comparison between the current DSM-5 and DSM-IVTR criteria.

| Authors | Diagnoses Included | Sample Size | Breakdown by Diagnosis | Age Range | OverallASD % Change(Negative) | AD %Change | PDD-NOS% Change | Asperger’s% Change |

| McPartlandVolkmar | ADPDD-NOSAsperger’s | 657 | 45015948 | 1-43 yrs.Mean 9.2 | (39.4%) | (24.2) | (71.7) | (75) |

| Matsonet al. | ADPDD-NOS | 795 | 453342 | 17-36Months | (47.8%) | (24.3) | (79.9) | N/A |

| WorleyMatson | N/A | 180 | N/A | 3-16 yrs.Mean 8.3 | (32.3%) | |||

| GibbsEt al. | ADPDD-NOSAsperger’s | 111 | 593418 | 2-16YearsMean 6.1 | (23.4%) | (10.2) | (50) | (16.6) |

| TaheriPerry | ADPDD-NOS | 131 | 9336 | 2.8-12.6YearsMean 6.4 | (37%) | (19) | (83) | N/A |

| Field Trials | ADPDD-NOSAsperger’s | 79 | 352321 | 6-17 yrs.Approx. Mean 12 | (19%) or5% increaseSee notes above | |||

| Mazefskyet al. | ADPDD-NOSAsperger’s | 498 | All three diagnoses were treated as one group. | 5-61 yrs.Mean 21.8 yrsMean IQ 105 | (0-7%) With the caveat that both the ADOS and the ADI-R be used together, including the non-algorithm ADI items for RRBS. Without the caveat, the drop in overall ASD diagnosis using the DSM-5 was an 11-14% drop. Using the ADI-R alone gave a 17% drop. | |||

| Authors | Diagnoses Included | Sample Size | Breakdown by Diagnosis | Age Range | OverallASD % Change(Negative) | |||

| Turyginet al. | ASD (DSM-IVR)ASD (DSM-IVR + DSM5) | 2054 | 278279 | 17-36 months | This study was designed to look at the levels of impairment of toddlers with DSM-IVR vs. DSM-IVR+DSM-5 diagnoses and other DD children. It found that toddlers who also met both sets of criteria had more difficulties on various measures of the Battelle Developmental Inventory than toddlers who only met the DSM-IVR criteria. | |||

| HuertaEt al.See notes | ADPDD-NOSAsperger’s | 4453 | 3221971251 | 2-17.11 Yrs.Mean6.4-9.43 sites | (9%) | |||

| BeighleyEt al. | ADPDD-NOSAsperger’s | 328 | Not given | 2-18Yrs.Mean8.01 | (33.2%) | Challenging behaviors were more similar between the ASD groups diagnosed by the DSM-IVTR criteria vs. the DSM-5 criteria than they were to controls who met neither set of criteria. | ||

| WilsonEt al. | ADPDD-NOSAsperger’s | 80 | Not given | 18-65Yrs.Mean 31 | (24%) usingDSM-IVTR(44%) vs.ICD-10R | |||

| BartonEt al. | ADPDD-NOSAsperger’s | 284 | Not given | 16.8-39.4MonthsMean 25.8Months | Sensitivity of the DSM-5 criteria did not get to .90 until the algorithm was relaxed to 2 of 3 speech/social and 1 of 4 RRB behaviors. | |||

Discussion

The DSM-5 criteria for autism spectrum disorders continue to be controversial. The studies reviewed here raise many questions. Certainly, by comparison, the DSM-5 criteria have not been vetted nearly as well as the DSM-IV criteria. Those criteria were tested at 22 field trial sites with over 1000 cases before they were implemented. The questions regarding the impact of the new criteria fall in three major categories: how will they affect services, how will they affect prevalence estimates and how will they affect other research.

Services

Based on the above studies, the new criteria are likely to reduce the number of individuals eligible for services under an ASD diagnosis. While IDEA defines ASDs in a more narrative fashion than DSM-5, arguably it will be more difficult for parents to obtain appropriate school services without a clinical diagnostic label. In terms of insurance coverage, the same comment applies. In addition, the shunting of cases to Social Communication Disorder is problematic because insurance companies routinely demand “evidence-based” treatments and there is currently no literature on the treatment of this disorder. This lack of research will likely result in these children being denied speech therapy coverage and behavioral treatments.

Prevalence

It is tough to predict how the DSM-5 criteria will affect the tracking of autism prevalence. Several scenarios are possible. Based on the research so far, it is likely we will see a significant reduction in autism diagnoses. However, it will be extremely difficult to assess the shift. The criteria are just being released this month and there will be a transition period that will take different amounts of time in different regions or clinical settings. There are three possible scenarios going forward:

1) If autism rates continue to go up, that will support the idea that the increase is not being driven by the diagnostic criteria, since the DSM-5 criteria are clearly more restrictive than the DSM-IVTR criteria. However, we will not know if the increase would have been greater without the change.

2) If autism rates start to level off, we will be unsure whether it is due to the new criteria or to an actual decrease in cases.

3) If there is a significant drop in autism rates, we will be unsure whether the criteria are responsible or whether something major has changed in the environmental triggers of autism to reduce cases.

In all these scenarios, the implementation of the DSM-5 criteria will hopelessly muddle an already unclear picture of the trends in autism diagnosis and make it nearly impossible to compare any environmental exposures to the prevalence rates over time.

To be clear, the CDC counts 8 year- olds so the next two rounds of their reporting should be largely unaffected by the DSM-5 changes (the 2010 8 year-olds and the 2012 8 year-olds) since those children will all have qualified for an ASD diagnosis under the DSM-IVTR criteria. However, starting with the 2006 birth cohort (2014 8 year-olds), there will be a mixture of children counted – those diagnosed at younger ages using the DSM-IVTR criteria and those diagnosed at age 7 or 8 using the DSM-5 criteria. That is the point at which we should start to see any reduction in cases as the result of the new criteria. This will be complicated by the variations in the average age of diagnosis from state to state. However, the DSM-5 will have an immediate impact on the numbers of the youngest children being diagnosed and the “missed older cases” being diagnosed starting this year.

Research

Lastly, the new criteria will complicate ongoing research. Any database that includes longitudinal records will have to figure out ways to compare those cases diagnosed before and after the implementation of the DSM-5 criteria. The studies to date also suggest that newly diagnosed cases (DSM-5 criteria) may be more severely impacted than the older cases (DSM-IVTR criteria) so it will be difficult to do meta-analyses over time since the populations that are included may not be comparable. The new criteria will likely increase costs in some studies as researchers take the extra time to do these additional diagnostic assessments.

Recommendations

For Parents:

- Document your child’s history so that if something happens to you there will be a record of symptoms your child had in the past. Keep a folder with all previous professional evaluations in one place in case your child needs to be re-assessed using the new criteria.

- For parents seeking a new diagnosis, recognize that a toddler may not obviously meet the new criteria. Be sure that both the ADOS and ADI-R are used along with a detailed history, if at all possible but keep in mind that these assessments will likely be updated to reflect the new criteria. If that isn’t possible, be sure to make a complete list before the evaluation of all behaviors your child exhibits. Note ways in which these behaviors impact your child’s functioning.

- If your child is one that may be diagnosed with Social Communication Disorder, document any speech issues that your child has and ask for a dual diagnosis along with an established speech language disorder in order to leave no question about speech services eligibility. Use the SCD diagnosis to advocate for additional social components to your child’s program.

For Clinicians:

- Consider that several studies have found greater sensitivity with a relaxation of the criteria. Particularly for toddlers, consider relaxing the RRB criteria to 1 out of 4 instead of 2 out of 4 and recognize that some toddlers may not have had many opportunities to meet the criteria for A3.

- Take a careful history since behaviors exhibited in the past that match the DSM-5 criteria are allowable, even if they are no longer present.

- Ask the families that you work with if they are having any trouble accessing services in your area as a result of the new criteria.

For Researchers:

- Be sure to reassess any subjects that are diagnosed during the transition years coming up, since it may not be clear which criteria a given clinician used.

- Add on to your projects to allow for diagnosis using both DSM-IVTR and DSM-5 to allow you to analyze any differences in your results based on the DSM version used. This will help inform research going forward and maximize the speed with which we can sort out the impact of the new criteria on severity, symptoms and so forth

- Report any differences in case ascertainment between the old and new criteria in the abstracts of your publications to inform the community and your colleagues.

- For epidemiologists, please do additional studies on the impact of the new criteria on minorities, different age groups, and different regions of the country. There is a huge void waiting to be filled.

For the Press:

- Be skeptical of all reports of autism rates dropping over the next decade. Make sure you educate yourself on the details of whatever you are reporting. Investigate any stories you hear about individuals with autism losing their diagnosis and/or services.

For Elected Officials:

- Look critically at any report of reductions in autism cases. Ask how old the cases are and which set of criteria was used for diagnosis. Be sure that you understand what you are looking at in the light of the diagnostic changes that DSM-5 includes.

- Review any autism-specific legislation, current or signed, and make sure that the language of the bill reflects your intentions, given the likely impact of the new DSM-5 criteria.

- Recognize that the elimination of higher-functioning children from the spectrum is likely to be a long-term problem for society, since those are the children most likely to “recover” as a result of intensive early behavioral therapy (ABA). If these children are no longer eligible for ABA due to their lack of ASD diagnosis, we can no longer expect them to make the same level of progress. Several of the studies above clearly showed that this is a population with significant needs relative to the typical population.

Perspective on the Numbers

One final, critical point needs to be made. Even if the DSM-5 ASD criteria dramatically reduce the number of identified cases, the number of individuals affected is still alarming. Consider the following:

1 in 88 children affected = 113.6 cases per 10,000.

If the rate drops 20%, then 90.9 cases per 10,000 still equals 1 in 110 children affected.

Even if the rate drops 40%, then 68.2 cases per 10,000 still equals 1 in 147 children affected.

So the urgency of the autism epidemic remains, while more individuals will likely fall through the cracks.

Overall, the community concerns about the impact of the DSM-5 ASD criteria remain justified based on the research literature to date. Only time will tell what the exact impact will be.

More Information

Changes in DSM-5 Autism Definition Could Negatively Impact Millions, Autism organizations concerned that autism diagnostic changes will jeopardize services, impair tracking, and disrupt research around the globe.

Comparison of Old and New Criteria

DSM-5 – Concerns and Questions From the Autism Community Follow Up with Dr. Susan Swedo – February 7, 2012